Subscribe to Recasting Regulations to Sign up for Loper Bright Updates.

"*" indicates required fields

Earlier this week at SCOTUSblog, Columbia University law professor Abbe Gluck suggested the Supreme Court’s recent opinion in Kennedy v. Braidwood Management might reflect what some have forecast as a “revival” of so-called “Skidmore deference.” On her reading of Kennedy, the Court’s examination of “considered and consistent Executive Branch practice—which beg[ins] contemporaneously with enactment of [a] statute”—should not only play an essential role for judges offering their independent judgment as to the best meaning of the law, as required by Loper Bright, but also hints at a reinvigoration of the deference—or “weight”—given to agency legal interpretations under Skidmore v. Swift & Co.

Although Professor Gluck is right to highlight Justice Kavanaugh’s emphasis on the utility of longstanding and consistent agency interpretations, it would be wrong to see such emphasis as a revival of Skidmore, let alone any other type of special solicitude for the views of agency “experts.” The Kennedy decision—along with other cases this term like McLaughlin Chiropractic and VanDerStok—is best understood as part of the Supreme Court’s efforts in the wake of Loper Bright to revitalize the traditional canons of statutory interpretation. Those canons, which play a vital role in the judicial act, long predate Chevron, Skidmore, or the modern administrative state.

Loper Bright and “Respect” for Agency Interpretations

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo stands for the simple proposition that federal judges must exercise independent judgment to provide their best reading as to the meaning of the law. Judges have various tools at their disposal to reach that best reading. Foremost among them are the canons of statutory construction. These are the rules of the road for how judges interpret legal texts while sticking to “lawfinding rather than lawmaking,” as Justice Gorsuch wrote in his Loper Bright concurrence.

Even though Loper Bright eliminated Chevron’s command to defer to an agency’s legal interpretation in a case of statutory ambiguity, it left room for judges to afford “due respect” to the views of the Executive Branch when trying to discern the meaning of an obscure or difficult term or phrase. As the court explained, “due respect” to an agency’s construction of the law can prove useful for resolving such obscurity, especially if an agency “interpretation was issued roughly contemporaneously with enactment of the statute” at issue and has “remained consistent over time.” Such respect might also be appropriate when an agency’s views are based on “factual premises” within its technical “expertise.” Yet the Loper Bright court made clear that “respect” never entails displacement of a court’s own best judgment. “Due respect” is not equivalent to the deference previously afforded to agencies under Chevron.

What about Skidmore?

At various points in its discussion of “respect” for agency legal interpretations, the Loper Bright majority cited an important administrative law case from the 1940s: Skidmore v. Swift & Co. In Skidmore, the Supreme Court identified several factors that counsel in favor of judges giving agency interpretations “weight” when deciding questions of law. Specifically, the Skidmore court explained agency “interpretations and opinions,” when “made in pursuance of official duty” and “based upon . . . specialized experience,” “constitute[] a body of experience and informed judgment to which courts . . . [can] properly resort for guidance.” The force of those interpretations, in turn, depends on “the thoroughness evident in [the agency’s] consideration [of the issue at hand], the validity of its reasoning, its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements, and all those factors which give it power to persuade, if lacking power to control.” Although the Court may not have intended Skidmore to function as a deference doctrine, in many cases the “power to persuade” tended towards a real power to control.

But what does that all mean now? The Loper Bright court’s repeated references to Skidmore, without any obvious unpacking of what that “deference” looks like after Chevron, may seem to verge on the irresponsible. It certainly fueled academic curiosity, with scholars like Professors Kristin Hickman and Bernard Bell considering how courts might revitalize or expand Skidmore’s domain.

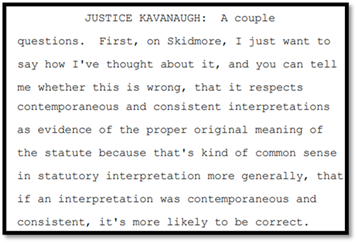

But it is hard to square a robust neo-Skidmore-deference doctrine with the overall thrust of Loper Bright. Every reference to Skidmore (save one) in Loper Bright is accompanied by a reiteration of the importance of the longstanding and contemporaneous qualities of an agency’s interpretation. None of the other Skidmore factors, such as procedural rigor or internal logic, are mentioned. That likely reveals the Loper Bright court’s intent to reign-in and limit any revival of Skidmore, or perhaps even to redefine it for the post-Chevron age. Judge Kavanaugh’s comments during the Loper Bright oral argument are telling, in this regard, especially as he wrote the opinion in Kennedy.

Justice Kavanaugh’s narrow reading of Skidmore stands in stark contrast to the aggressive version found in United States v. Mead Corp. There, Justice Souter enumerated a host of factors that might trigger a “fair measure of deference” to an agency whenever a question arises over the meaning “its own statute,” such as the “degree of the agency’s care, its consistency, formality, and relative expertness.” Justice Scalia, in dissent, castigated this approach as ill-defined, especially as to the level of deference actually afforded to an agency. Skidmore, as refined by Mead, was akin to “that test most beloved by a court unwilling to be held to the rules (and most feared by litigants who want to know what to expect): th’ol ‘totality of the circumstances’ test.” This criticism holds true today. A resurrected totality-of-the-circumstances Skidmore that functions just like Chevron would be “a recipe for uncertainty, unpredictability, and endless litigation.”

The October 2024 Term—Whither Skidmore?

This brings us to the Court’s recently completed term. Does Kennedy represent a meaningful revival of Skidmore? The evidence would suggest not.

To begin with, the Supreme Court has not once cited Skidmore since Loper Bright was decided. It would be curious indeed if the Court intended to leave the door open to neo-Skidmore deference, but without any citation to the seminal decision. Similarly, it is hard to countenance how “due respect” could translate to a revitalized deference regime after the Court’s explicit clarification in Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County that judicial review under Section 706 of the APA really does mean de novo review. The silence of Loper Bright on this point left some pro-Chevron commentators hopeful that Skidmore could serve as a vehicle for reintroducing deference. That seems unlikely at this point.

This term’s decisions instead reflect a decided effort by the Court to stress the basic aspects of statutory construction and to revive traditional interpretive canons. Consider, for example, McLaughlin Chiropractic Associates v. McKesson Corp., which directs courts to “determine the meaning of the law under ordinary principles of statutory interpretation.” To the extent “appropriate respect” is due to an agency’s interpretation of the law, that respect must be realized in the application of the canons. McLaughlin is particularly insightful on this point, as it resolved a circuit split over whether, under the Hobbs Act, district courts in private enforcement proceedings were bound by prior agency interpretations reached in administrative adjudicative proceedings—the sort of context in which “due respect” under Skidmore would have been cited.

The decisions in Bondi v. VanDerStok and Kennedy are noteworthy for a different reason. In each of these cases, the Court explained how and when an agency’s interpretation of the law might be useful in statutory construction. Specifically, the Bondi court explained “the contemporary and consistent views of a coordinate branch of government can provide evidence of the law’s meaning.” And the Kennedy court spoke of how “considered and consistent . . . practice” that “began contemporaneously with enactment” of the statute might “buttress[] the ordinary meaning and natural interpretation” of the legal language. Neither of these statements hints at Skidmore deference. Neither of them suggests an agency’s view of the law is intrinsically valuable.

Instead, both VanDerStok and Kennedy support the idea that an agency’s longstanding and consistent reading of a statute is only useful insofar as it is probative of the original public meaning of the law. Agencies are first-in-time implementers and principal executors of the law; it is commonsensical that they might have valuable insight into a statute’s meaning, especially when a reviewing court sits far in time from enactment of any given law. But an agency interpretation deserves no “respect” for its own sake, that is, because it represents the views of an “expert” agency, let alone a coordinate branch of government.

The Court’s reference to “due respect” in Loper Bright, and its repeated appeal to longstanding and consistent agency practice in the past term, is an attempt to reestablish two longstanding interpretative canons that predate the advent of modern administrative law and Skidmore: the contemporanea expositio and interpres consuetudo canons. Professor Aditya Bamzai has written extensively about the provenance and contours of these canons, which were traditionally “considered part and parcel of de novo review.” Members of the Court, too, have highlighted the importance of the canons long before Loper Bright. Justice Kavanaugh, for example, explained in his concurrence in Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency, how a “longstanding and consistent agency interpretation” might “reflect[] and reinforce[] the ordinary meaning of the statute.” And Justice Thomas, when dissenting from the denial of certiorari in Baldwin v. United States, analogized the use of these canons to “the more general principle of ‘liquidation,’ in which consistent and longstanding interpretations of an ambiguous text could fix its meaning.”

Conclusion

The trend at the Supreme Court is clear—there is no revival of Skidmore underway, but rather a reinvigoration of the traditional contemporanea expositio and interpres consuetudo canons. Of course, things will be messy in the lower courts in the near term. The Ninth Circuit has already issued what might be described as a “Skidmore maximalist” opinion in Lopez v. Garland. And, on the other end of the spectrum, the Fifth Circuit, in Mayfield v. Department of Labor, asked “what work Skidmore can do” any longer. The law admittedly moves slowly. But over time—and assuming the current composition of the court is maintained and its textualist temperament continues—it is unlikely that any serious Skidmore-deference doctrine will grow roots.

A federal judge in the District of Rhode Island ruled in favor of the government yesterday in Relentless v. Department of Commerce, the companion case to Loper Bright v. Raimondo, which was sent back to lower courts on remand after the Supreme Court’s historic decision last year. With the end of Chevron, the district court was tasked with re-evaluating the government’s arguments for whether the National Marine Fisheries Service (“NMFS”) had authority to require certain commercial fishermen to pay the salaries of the government-approved monitors who ride their boats to watch them fish.

The judge in Relentless identified two bases for the legality of the industry-funding mandate. First, it looked to a provision of the Magnuson-Stevens Act (“MSA”), Section 1853(b)(8), which permits a fishery management plan to “require that one or more observers be carried on board a vessel . . . for the purposes of collecting data[.]” The court did not purport to construe the phrase “be carried on board,” nor did it apply any traditional canons of construction. It rather concluded, in summary fashion, that industry funding was defensible as a kind of compliance cost. In so doing, it relied solely on Judge William Kayatta’s concurrence in Goethel v. Department of Commerce, and his assertion that “the default norm, manifest without express statement in literally hundreds of regulations, is that the government does not reimburse regulated entities for the cost of complying with properly enacted regulations, at least short of a taking.”

Second, the district court concluded the industry-funding mandate was permitted by the MSA’s catchall “necessary and appropriate” provision, which it determined, “in no uncertain terms, delegates . . . a large degree of discretionary authority.” The court did not, however, address the boundaries of that discretion but simply reiterated its prior decision that adoption of industry funding “reflect[ed] reasoned decisionmaking” under the Administrative Procedure Act’s arbitrary-and-capricious standard of review.

The fishermen’s various other arguments about broader statutory context were unavailing. The district court noted that, in its estimation, the existence of a penalty provision for nonpayment of “observer services provided to or contracted by an owner of operator” would make little sense if Congress had not intended to provide NMFS with discretion to promulgate a rule like the industry-funding mandate. The court buttressed that conclusion with the broader “purpose” and “policy undergirding the MSA.” The district court also dismissed the fishermen’s negative-implication arguments that focused on narrower, specific grants of industry-funding authority for foreign fishing vessels, limited access privilege programs, and fisheries in the North Pacific. Finally, the court rejected any reliance on legislative history, which is “‘not the law.’”

A Few Observations

It is quite striking how the district court in Relentless omitted any in-depth analysis of its construction of the MSA. It did not grapple with the actual text of the Act and, more disturbingly, did not explain how it was applying (or not!) the traditional canons of statutory construction. For example, with the notion of compliance costs, the court neglected to explain why a vessel’s obligation to “carry” an observer entails, as a textual matter, the concomitant duty to cover the observer’s “travel costs and daily salar[y].” The court did claim the fishermen’s argument on this point—specifically, that paying a monitor’s salary was qualitatively different than any reasonable, common-sense compliance cost—“‘face[d] an uphill textual climb,’” yet it hardly fleshed that out in any meaningful way. Why did that argument face textual difficulties? What, exactly, does it mean to “carry” an observer? What other financial responsibilities do vessel operators and owners have with respect to observers? These questions remain unanswered.

Even more alarming is the district court’s analysis of the MSA’s “necessary and appropriate” provision. Although the court acknowledged its duty under Loper Bright to “recogniz[e] constitutional delegations, [and] fix[] the boundaries of the [agency’s] delegated authority,” it did not do so here. Judge Smith mischaracterized the entire legal dispute, transforming a fight over legal meaning—i.e., what do “necessary” and “appropriate” mean in the context of discretionary elements of fishery management plan—into a question of “hard look” review. Indeed, the Relentless opinion contains scant discussion about any limits of the government’s authority, apart from a cross-reference to the policy goals undergirding the MSA, as well as its National Standards. The court did reject the fishermen’s arguments as effectively “read[ing] Subsection (b)(14) out of the statute,” but that hardly amounts to positive engagement with the statutory text. And that is perhaps the most pernicious aspect of the Relentless decision. It leaves the door open to much regulatory mischief that can be justified in the ambiguous name of whatever is deemed by NMFS as “necessary and appropriate” for the conservation and management of domestic fisheries.

Read the district court opinion here.

At SCOTUSblog, Abbe R. Gluck writes about Kennedy v. Braidwood Management, and ” the broader question of how the court will grapple with questions of expertise in the wake of its 2024 decision overruling Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, the key agency-deference case of the modern era.”

Finally, for good measure, the opinion concludes with a touch of implicit Skidmore deference, the pre-Chevron deference regime under which courts give weight to agency interpretations, especially consistent ones, but only to the extent they have the “power to persuade.” Citing Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the decision that overruled Chevron, Justice Kavanaugh noted, “the Executive Branch’s actions for the last 26 years … have reflected that straightforward interpretation of the statute—without any apparent objection from Congress … to ‘convene’ the Task Force to include the power to appoint the Task Force members. That considered and consistent Executive Branch practice … buttresses the ordinary meaning and natural interpretation of the term ‘convene’ in the statute.”

This methodology thus follows a trend that has emerged in several other cases this term as the court resets after Loper Bright: The court now insists, in what many view as a revival of Skidmore, that it is construing the statute independently but looks to a consistent agency interpretation as evidence of the correctness of that interpretation.

Bloomberg Law’s Robert Iafolla writes about how “circuit courts have started going in different directions on the level of deference judges should grant agencies.”

Federal appeals courts are still figuring out how much weight to give to agencies’ views of their legal authority, a year after the US Supreme Court said judges must interpret relevant laws.

…

“The lower courts aren’t certain what to do with Skidmore after Loper Bright,” said Kristin Hickman, an administrative law professor at the University of Minnesota. “What we’re seeing reflected in the Ninth Circuit and Fifth Circuit is emblematic of that uncertainty.”

…

Loper Bright instructed courts to treat Skidmore as an optional canon of construction, said Eric Bolinder, an administrative law professor at Liberty University. That’s how the justices themselves used Skidmore—without citing it—in a March decision upholding regulations on ghost guns, he said.

Harvard Law School’s Matthew Stephenson recently published “The Gray Area: Finding Implicit Delegation to Agencies After Loper Bright.” From the abstract:

This Article argues that the canonical pre-Chevron cases Gray v. Powell and NLRB v. Hearst Publications, together with their antecedents and progeny, provide a useful framework for distinguishing those interpretive questions on which courts ought to find implicit delegations to agencies from those issues that are for the courts to decide without deference. The Gray doctrine establishes a presumption that, when a statute empowers an agency to take some authoritative action which necessarily involves the application of an imprecise statutory term to particular situations, the statute should be read as implicitly delegating to the agency the authority to make the necessary line-drawing decisions. At the same time, the Gray doctrine does not call for judicial deference to an agency’s views on the resolution of interpretive questions that can be answered through abstract textual or structural analysis.

Courts can and should incorporate the Gray doctrine into the implicit delegation prong of the Loper Bright framework. Doing so would be both legal—consistent with the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) as interpreted by Loper Bright—and desirable. The Gray doctrine provides a structured, workable method—one well-grounded in decades of pre-Chevron case law—for deciding when a finding of implicit delegation is appropriate. Integrating Gray into Loper Bright would achieve a more appropriate allocation of authority between the judicial and executive branches than would alternative and more restrictive approaches to Loper Bright’s implicit delegation prong.

This past Term, the Supreme Court cited Loper Bright in several statutory interpretation decisions, including Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County, Bondi v. VanDerStock, McLaughlin Chiropractic Assocs., Inc. v. McKesson Corp., and City and County of San Francisco v. EPA. Loper Bright surfaced again on the last day of the Term in FCC v. Consumers’ Research, a case involving a nondelegation and private nondelegation challenge to the Universal Service Fund—a telecommunications social welfare program funded by a charge set by unelected administrators at the FCC (who, in turn, punted that task to a private corporation made up of self-interested industry insiders).

Consumers’ Research presented the Court with an opportunity to reinvigorate the nondelegation doctrine by enforcing Article I’s bar against Congress transferring its exclusive legislative power to other entities. The Court did not take that path. Instead, in a 6–3 decision, the Court declined to revisit the “intelligible principle” regime, rejecting Consumers’ Research’s nondelegation and private nondelegation challenges, as well as the Fifth Circuit’s “combination theory” of unconstitutionality.

Justice Kagan’s and Kavanaugh on Loper

Writing for the six-Justice majority, Justice Kagan cited Loper Bright in the course of construing the statute to grant the FCC far more limited powers than under the dissent’s (and Fifth Circuit’s) interpretation—a move that diminishes constitutional concerns. Justice Kagan suggested that at oral argument the Solicitor General had taken the position that the statute imposed certain limits on the agency’s powers but emphasized, quoting Loper Bright, that “[i]n any event, and yet more important, we must ‘exercise [our] independent judgment in deciding’ what power Congress has conferred”—a key overarching point of Loper Bright. In a footnote, the dissent echoed this core point in Loper Bright but parted ways on its application in this case to the Solicitor’s statements.

Justice Kavanaugh’s solo concurrence also cites Loper Bright, offering some insight into its broader significance and impact. As Professor Josh Blackman has observed, Justice Kavanaugh’sthoughtful Consumers’ Research concurrence is interesting for a number of reasons. Justice Kavanaugh suggests that, in his view, “[m]any broader structural concerns about expansive delegations” of power by Congress to the Executive branch “have been substantially mitigated” by the Supreme “Court’s rejection of so-called Chevron deference” in Loper Bright, as well as the Court’s use of the “major questions canon.” And citing passages in Loper discussing courts’ duty under the Administrative Procedure Act to independently interpret statutes and role in policing delegations of discretion to the Executive, Justice Kavanaugh notes that while intelligible-principle test doesn’t do much to stop Congress from delegating power to the Executive, “the President’s actions when implementing legislation are constrained—namely, by the scope of Congress’s authorization and by any restrictions set forth in that statutory text.” Justice Kavanaugh also suggested that broad delegations to “independent” agencies raise greater constitutional concerns, to the extent those administrative bodies can constitutionally exist.

Will Consumers Research “Stand the Test of Time?”

In his dissent in Consumers’ Research, Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justices Thomas and Alito, cites his concurring opinion in Loper Bright, which gives a thoughtful, scholarly exposition of his views on stare decisis and why courts shouldn’t overread stray remarks and dicta as holdings. Justice Gorsuch wrote that “things could be worse. Because today’s misadventure ‘sits unmoored from surrounding law,’ I have reason to hope its approach will not stand the test of time.” This reminds that the now-overruled Chevron doctrine requiring courts to grant “deference” to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes was built on an overreading of stray dicta in its namesake Chevron v. NRDC. And at the risk of being an optimist, one wonders whether Consumers’ Research may end up being something of a one-off that we should not overread. Time will tell. But what is clear at Loper Bright’s one-year mark is that while the result in Consumers’ Research was disappointing to many, Loper Bright is a landmark victory reaffirming that it is up to the Judiciary—and not the Executive—to say what the law is and independently determine the metes and bounds of the discretion and powers Congress has granted the Executive. While Loper Bright is not a panacea for the ill effects of the current distortion in our system of separated powers and federalism, it is an important, much-needed step in the right direction that, to borrow Justice Kavanaugh’s language, “mitigates” some of those problems.

Two commenters from the NYU School of Law’s Institute for Policy Integrity have a piece on the Yale Notice & Comment blog challenging the Trump Administration’s invocation of Loper Bright as a nondiscretionary basis to rescind the existing regulatory definition of “harm” as it applies to the Endangered Species Act.

Jack Jones and Max Sarinsky write:

The agencies seek to rescind the definitions of “harm” in the Endangered Species Act regulations, based on their conclusion that the current definitions “do not match the single, best reading of the statute,” per Loper Bright. But as the notice acknowledges, the Supreme Court upheld the current regulatory definitions in Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter of Communities for a Great Oregon. And even though Loper Bright emphasized that cases like Sweet Home remain good law, the agencies claim that the rescission is “compelled” by law because they have concluded that the definitions do not reflect the best reading of the statute. The agencies then go further, asserting that the rescission is thus a “nondiscretionary action,” meaning they “do[] not have authority” to consider otherwise relevant policy or factual issues such as the repeal’s environmental effects.

But the agencies’ conclusion misunderstands Loper Bright’s discussion of statutory stare decisis. Because the current regulatory definitions were previously upheld in Sweet Home, they remain good law after Loper Bright. The agencies could choose to maintain them and are not legally compelled to rescind them even if, as the agencies claim, they are inconsistent with the statute’s best reading. Accordingly, the agencies’ decision to rescind the regulations is voluntary, not “nondiscretionary”—and the agencies therefore do need to rationally consider relevant policy and factual issues in order to satisfy the requirements of reasoned decisionmaking.

Americans for Prosperity Foundation filed a regulatory comment supporting the rescission. And Recasting Regulations has also featured the Jonathan Nash article on Chevron and stare decisis upon which Jones and Sarinsky rely.

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo’s Legacy Empowers Courts, Congress to Reclaim Proper Constitutional Roles

Washington, DC, June 27, 2025 — Tomorrow marks the first anniversary of the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, a transformative decision that ended four decades of Chevron deference. By restoring to courts the duty to interpret the law and provide an independent judgment as to its best meaning, the Supreme Court helped realign the proper balance of power between Congress, the administrative state, and the federal judiciary.

“The Loper Bright decision changed the landscape of administrative law. It will be remembered as a watershed moment in Supreme Court jurisprudence,” said Ryan P. Mulvey, senior policy counsel at Americans for Prosperity Foundation and senior counsel at Cause of Action Institute. “The Court was right to reiterate the Founders’ vision of judges—not bureaucrats—telling us what the law means. The end of Chevron deference is an important step to helping us keep regulatory agencies in check and within the bounds of the authority given to them by Congress.”

Over the past year, Loper Bright has influenced developments across the federal government. Courts at the federal and state levels have cited the precedent in nearly 1,000 cases. In some of the more impactful decisions, the new Loper Bright standard was used to invalidated the Federal Communications Commission’s net neutrality rules, and to reject the Food and Drug Administration’s novel attempt to regulate laboratory testing services as manufactured “devices.”

Loper Bright has played a prominent role in the Trump Administration’s deregulatory agenda, too. The Environmental Protection Agency pointed to Loper Bright as the basis for its reconsideration of a controversial “endangerment finding” on greenhouse gases, and the Department of the Interior is using it to rescind a long-contested regulatory definition of “harm” under the Endangered Species Act. President Trump even identified Loper Bright as one the principal bases for the DOGE deregulatory initiative kicked off by Executive Order 14219.

And the end of Chevron deference has not escaped the attention of Congress either. The “Post-Chevron Working Group,” led by Senator Eric Schmitt, published a lengthy report earlier this month detailing the importance of Loper Bright and how it can be leveraged by federal legislators to reclaim their Article I authority. Former Senators Heitkamp and Martinez led similar efforts at the Bipartisan Policy Center, recommending practical solutions for a post-Chevron Congress.

Despite these impressive developments, it is vital to remember the Loper Bright case was always about Atlantic herring fishermen threatened by an unlawful regulatory requirement that could force them to surrender 20 percent of their earnings to pay for at-sea monitors to ride their boats and watch them fish. The government relied on Chevron deference to justify its controversial monitoring rule. Yet, with Chevron overruled, the saga of the fishermen continues, and the fate of the industry-funding requirement hangs in the balance. The D.C. Circuit considered the fishermen’s supplemental briefs and heard oral argument on remand last fall, and an opinion is expected in the near future. “By returning interpretive power to courts, Loper Bright reaffirmed the separation of powers and the rule of law,” said Mulvey. “Now, the real test is ensuring the fishermen aren’t left paying for regulatory programs with no firm statutory basis.”

First, we have Bernard W. Bell from the Rutgers Law School – Newark in the Seton Hall Law Review on “Loper Bright: Resurrecting Skidmore in a New Era.” Some excerpts from the abstract:

In Loper Bright v. Raimondo (2024), the Supreme Court abandoned Chevron deference to agency statutory interpretations, resurrecting the Skidmore “persuasive” deference regime. This article offers three observations.

First, the judicial context has changed since Chevron’s adoption, such that the new” Skidmore deference will produce quite different results than the old.

…

Second, the “major questions doctrine” will make inroads on Skidmore deference when the text favors agencies. The Court’s rejection of Chevron (and reinstatement of Skidmore), was based on the concept that “the law” never simply “runs out.” That proposition directly contradicts the premise of the major questions doctrine, that in some instances the law does indeed “run out” and Congress must create “new” law to directly address crucial issues.

…

Third, the article explores the treatment of Chevron-based interpretive precedents in this second Skidmore era. In Loper Bright, the Court adopted an apparently categorical rule, that Chevron-based precedents remain “good law.” In so choosing, the Court might have sought to avoid the failures of its more nuanced, and ultimately quite unsatisfactory, Brand X approach to Skidmore-based precedent in a Chevron world. However, the Loper Bright categorical rule is less categorical than it seems.

Next, we have Matthew Mulholland from the Lincoln Memorial University Duncan School of Law with “Beyond Saving Ink: How the Current Court Finds Meaning in Statutory Variations Post-Loper Bright.” From the abstract:

This case comment analyzes the Supreme Court’s decision in San Francisco v. EPA, a pivotal moment illustrating the Court’s renewed emphasis on strict statutory interpretation and finding significance in subtle textual variations to limit agency power in the post-Loper Bright era. The case centered on the EPA’s attempt to impose “end-result” prohibitions in San Francisco’s NPDES permit, forbidding discharges contributing to water quality violations or creating pollution under state law. San Francisco argued that these provisions exceeded the EPA’s authority under 33 U.S.C. § 1311(b)(1)(C) of the Clean Water Act, contending that “any more stringent limitation” does not authorize such broad mandates lacking specific, measurable limitations on the facility’s discharges. Applying a strict textualist approach, the Court held that § 1311(b)(1)(C) does not permit the EPA to impose end-result requirements focused on the ultimate condition of the water body rather than the permittee’s specific discharges, emphasizing Congress’s intentional omission of “effluent limitations” in this subsection compared to preceding ones. This decision highlights the Court’s readiness to override decades of agency practice if it conflicts with the statutory text, signaling increased judicial scrutiny of agency interpretations in environmental and administrative law post-Loper Bright, potentially leading to narrower, more literal interpretations absent a clear statutory basis for agency actions. Justice Barrett’s partial dissent advocated for a broader interpretation of “limitation” to encompass the EPA’s end-result requirements as necessary for meeting water quality standards, but the majority’s ruling underscores how the Supreme Court expects the judiciary to take an assertive role in interpreting statutory language and limiting agency power.

The Federalist Society is hosting a Webinar on July 1 at 2:00 PM ET on Loper and the NLRB.

Administrative law is in flux, nowhere more so than at the National Labor Relations Board. The Board has long made labor law (or “policy”) by issuing decisions and applying its own precedent. But in a recent oral argument at the Seventh Circuit, one member of the panel suggested that he didn’t want to hear about “Board law.” The judges, he said, could read the statute for themselves. That statement was controversial and thought-provoking. After last term’s blockbuster decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, courts are no longer supposed to defer to administrative agencies on legal questions. So does that mean Board law is dead? Or is the issue more complicated? Join our panelists as we dissect the issue.

Featuring:

- Prof. Samuel Estreicher, Dwight D. Opperman Professor of Law Director, Center for Labor and Employment Law Co-Director, Institute of Judicial Administration, NYU School of Law

- Alexander T. MacDonald, Shareholder & Co-Chair of the Workplace Policy Institute, Littler Mendelson P.C.

- (Moderator) Karen Harned, President, Harned Strategies LLC