Subscribe to Recasting Regulations to Sign up for Loper Bright Updates.

"*" indicates required fields

The Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright was a landmark victory for the rule of law, due process, and the separation of powers. But it was not the only important administrative law decision in the 2023 Term. Following Loper Bright, Corner Post, Inc. v. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System opened up the courthouse doors to people newly harmed by old regulations, holding that Corner Post’s 2021 challenge to a 2011 debit-fee regulation known Regulation II was timely because the APA’s six-year statute of limitations starts to run when a party is first harmed by the regulation—as opposed to when the agency promulgates it—and Corner Post didn’t open for business until 2018. Corner Post’s challenge to the Fed’s regulation was then remanded to the district court to decide on the merits. This time, Corner Post also had the benefit of Loper Bright’s instruction that courts must independently interpret statutes without granting deference to an agency. That appeared to matter.

District Court Ruling

Last week, on remand the district court granted Corner Post’s summary judgment motion, applying Loper Bright and concluding that Regulation II was beyond the agency’s power and thus unlawful. The result may have been different under Chevron. As the district court put it, “[w]hen this litigation began roughly fourteen years ago, the Parties were subject to the mire of Chevron deference.” Indeed, as the district court observed, the D.C. Circuit found in related litigation that the Fed’s debit-fee regulation rested on a “reasonable” interpretation of the statute that passed muster under Chevron.

But as the district court emphasized, Loper Bright “reinstituted courts’ proper role in statutory interpretation.” Quoting Marbury, the court added: “Courts—not agencies—emphatically and completely fill the role of saying ‘what the law is.’” And after Loper Bright, “[p]urported statutory ambiguities no longer change the legal calculus for how courts ought to review agency action.” The opinion’s discussion of Loper Bright’s impact on how courts interpret statutes and restored the judicial role under Article III to independently interpret the law continued. Citing and quoting Loper Bright, the district court observed that “[r]egardless of whether intentionality or lapse of mind created the supposed ambiguity, only courts hold the expertise and constitutional permission to resolve it. Accordingly, this Court—and not the Board—will determine the ‘best’ interpretation of the Durbin Amendment because courts hold the monopoly ‘[i]n the business of statutory interpretation’ and delineate the boundaries of an agency’s authority.”

Against this backdrop, the district court rejected the Fed’s argument that “Congress drafted the Durbin Amendment with the intention that the Board’s statutory interpretation would be reviewed deferentially,” agreeing with Corner Post that this was simply an attempt at “repackaging the defunct-Chevron deference under a different name.” It found that while Congress granted the Fed some discretion to regulate debit-card fees, the Durbin Amendment was not a “blank check” allowing the Fed to set whatever fees it wanted, rejecting the agency’s appeals to the statute’s purpose to justify its power claim. As the district court described it, “[t]he Durbin Amendment is akin to a funnel—it starts with a broad purpose and narrows to particular boundaries for the Board’s actions.” And the broad general and introductory statutory language is “not the Board’s permission slip to draft regulations with presumed deferential review.” Applying traditional canons of construction and independently analyzing the statute’s plain language and structure, the district court concluded that Regulation II exceeded the Fed’s authority under the Durbin Amendment and vacated it, finding it unnecessary to address Corner Post’s major questions and arbitrary and capricious arguments and staying its order pending appeal.

Reforms Making an Impact

Corner Post’s saga and recent victory illustrates that after Loper Bright and Corner Post ultra vires regulations reflecting agency statutory interpretations that could, at best, only be defended as “reasonable” under the now-discredited Chevron regime are not immune from judicial scrutiny merely because they have been on the books for a long time. Together, Loper Bright and Corner Post provide everyone harmed by stale regulations they believe to be unlawful with a meaningful pathway to get relief without first having to violate those regulations and risk an enforcement action or filing a rulemaking petition.

In Prichard v. Long Island University, a U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York relied on Loper Bright v. Raimondo to invalidate an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) regulation that had allowed the agency to issue “right to sue” notices before 180 days had passed. The decision made clear that EEOC regulations should not be given Chevron deference and that courts must exercise independent analysis in interpreting and applying EEOC regulations.

The court explained that “Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act of 1964] directs the EEOC to issue a RTS [Right to Sue] letter in two circumstances: if the EEOC dismisses the case or if 180 days have passed since the filing of a complaint and the EEOC has not completed its investigation.” In this case, the EEOC had not dismissed the case but nevertheless issued the RTS notice after only 57 days. In doing so, it relied on an EEOC regulation that allowed it to issue RTS notices when it has “determined that it is probable that the Commission will be unable to complete its administrative processing of the charge within 180 days from the filing of the charge.” 29 C.F.R. § 1601.28(a)(2).

The court noted that the circuits were split on whether this regulation was valid. Those that had upheld it had done so by finding “the statute ambiguous and deferring on to [sic] the agency’s interpretation under Chevron.” Explaining that, after Loper Bright, Chevron deference was no longer appropriate and therefore “[c]ourts, not agencies, determine statutory meaning,” the court found “the EEOC’s rule authorizing early RTS letters conflicts with the statutory text” because the regulation granted the EEOC additional authority beyond the statute’s two express conditions for issuing the notice (dismissal of the case or passage of 180 days).

Notably, in rejecting the plaintiff’s counter-argument, the court relied heavily on Loper Bright:

[Plaintiff’s] assertion that deference is due the EEOC’s interpretation of the statute effectively urges this court to operate in a parallel universe in which Loper Bright had been decided the other way. No case that [Plaintiff] cites (or that the Court has identified) sided with the EEOC on textual grounds without according deference: they either deferred to the agency pre-Loper Bright, or relied primarily on policy considerations. [Citations omitted] Neither approach now suffices to overcome the plain text of the statute.

Following her appearance at the HSGAC hearing on the future of Loper Bright, former OIRA Administrator Susan Dudley had a series of recommendations for how Congress can reassert itself and fulfill its constitutional role.

“First, legislation should recognize that while scientific facts are a necessary element of good policy design, they are almost never sufficient.”

“Second, Congress should provide agencies with clear guidance on how they should weigh competing considerations.”

“Third, … Congress should require agencies to evaluate their regulations periodically to determine how effective they are at achieving legislative goals, and to identify needed revisions both to the regulations and the underlying statutory authority.”

“Fourth, to support these efforts, Congress itself needs more resources[.]”

On July 23rd, in Zimmer Radio of Mid-Missouri v. FCC, the Eighth Circuit applied the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright to a dispute over the FCC’s quadrennial review of its media ownership rules in a way that highlights a few key themes in Loper Bright statutory interpretation cases.

- Courts generally review an agency’s interpretation of a statute (a legal question) de novo, independently fixing the metes and bounds of the agency’s power and discretion using traditional canons of interpretation.

- An agency’s contemporaneous and longstanding interpretation may shed light on a statute’s best reading.

- Subject to constitutional limits, where a statute is best read to delegate discretion to an agency, how the agency exercises that discretion under the deferential arbitrary and capricious standard so long as the agency stays within the boundaries set by the statute, particularly for agency decisions that turn on factual findings, policy decisions, and/or implicate technical expertise.

Background on the FCC Order

Under Section 202(h) of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, every four years the FCC is statutorily required to review its rules. Congress instructed that, as part of that review, the FCC “shall determine whether any of such rules are necessary in the public interest as the result of competition” and “shall repeal or modify any regulation it determines to be no longer in the public interest.” After conducting its 2018 review, the FCC decided to keep all of those rules on the books and tighten one of them. Petitioners challenged the FCC’s 2023 Order on multiple grounds, some of which elucidate Loper Bright’s impact.

Eighth Circuit Decision on Agency Discretion

In rejecting the petitioners’ argument that the FCC’s 2023 Order’s narrow definition of “market” was inconsistent with Section 202(h), the Eighth Circuit read Loper Bright to, on the one hand, require courts to rigorously police the boundaries of an agency’s statutory authority and independently decide what the law is. But the Court also cited Loper Bright for the proposition that Congress often writes laws “intentionally [to] provide agencies with discretion.” And as Loper Bright teaches, “[w]hen the best reading of a statute is that it delegates discretionary authority to an agency,” the APA requires courts “to independently interpret the statute and effectuate the will of Congress subject to constitutional limits.”

Applying these principles, the Eighth Circuit found that Section 202(h) is one such law, concluding that given the FCC’s “broad power to regulate in the public interest,” the agency “is best positioned to define ‘competition’ for purposes of Section 202(h).” The Court also invoked Loper Bright’s teaching that an agency’s contemporaneous and consistent interpretation can be evidence of a statute’s meaning as further supporting the FCC’s exercise of discretion to define “competition” for purposes of Section 202(h). As the Eighth Circuit put it, “[t]he Section 202(h) dispute here deals not with the meaning of competition, but with the degree—how much competition must be considered in analyzing the ownership rules subject to Section 202(h) review. . . . In essence, the question is one of line drawing.” Thus, while the FCC had to consider competition in its quadrennial review, it had discretion to decide how broad or narrow the relevant markets are. The Court framed that as a technical, policy-laden decision that Congress may delegate.

The Court next addressed petitioners’ alternative argument that the FCC’s market definition was arbitrary and capricious. Quoting the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County, Colorado (a case which may further elucidate Loper Bright’s meaning), the Court also noted “[w]hile judicial review of an agency’s statutory interpretation is generally de novo, ‘when an agency exercises discretion . . . , judicial review is typically conducted under the Administrative Procedure Act’s deferential arbitrary-and-capricious standard.’” Applying this deferential standard, the Court “decline[d] to second-guess the FCC’s market definitions,” later noting that it was not judicial role to determine what decision the agency should have reached.

The Court decided another statutory authority question in petitioners’ favor, quoting Loper Bright to reiterate that “[i]n evaluating the Section 202(h) challenge, we ‘must exercise [our] independent judgment in deciding whether [the FCC] has acted within its statutory authority.’” Petitioners argued that a provision of the 2023 Order that expanded a regulation exceeded the FCC’s authority under Section 202(h). The Court agreed. Again independently interpreting Section 202(h) to fix the bounds of the FCC’s authority, the Court concluded that it “provides for a two-step process. First, the Commission determines whether any of the regulations subject to review are necessary in the public interest as the result of competition. If the rules are no longer necessary, the Commission has two choices: repeal or modify.” Those choices are binary. By contrast, “[i]f the rules remain necessary in the public interest, . . . the inquiry and the FCC’s authority end.” In that case, the rule must remain in its current form unchanged. In other words, while Section 202(h) grants the FCC broad discretion in some areas, it is a one-way deregulatory ratchet that cannot be used to tighten regulations already on the books. The Court also rejected the FCC’s interpretation of “modify” to include the power to tighten regulations, using traditional tools of statutory construction. Based on that statutory interpretation, the Court found that the FCC’s decision to tighten a regulation it deemed “necessary in the public interest” was ultra vires.

The Eighth Circuit’s thoughtful decision in Zimmer Radio is yet another example of Loper Bright’s continuing and emerging impact on administrative law and statutory interpretation.

Here’s how the Wall Street Journal Editorial Page described the exchange:

Mr. Nixon’s tariffs for the most part also didn’t exceed the tariff “schedule that had already been enacted,” said another judge. Mr. Trump’s do. Mr. Shumate’s fall-back was that IEEPA was meant to be interpreted “very broadly.” But “is that really how we interpret statutes anymore?” and “do you think that standard survives Loper Bright?” judges asked.

The High Court’s Loper Bright (2024) landmark says that judges shouldn’t automatically defer to regulators’ interpretations of vague laws. The Court’s major questions doctrine also holds that Congress must give the President express authority for actions with economic and political significance. Mr. Shumate said neither precedent applies to a President’s power to conduct foreign policy.

Video below starts from the beginning of the exchange on Loper. Full oral argument audio here.

The first several months of the Trump Administration have focused on executive orders, agency reorganization, and budget reconciliation. But attention is now shifting to the meat of Executive Branch reform: deregulation. The Washington Post reports that DOGE has built a deregulatory tool that harnesses AI to assist agencies in identifying and eliminating unnecessary or unlawful regulations.

The July 1st DOGE presentation, obtained by the Post, highlights the AI tools and cites Loper Bright and Executive Order 14,219 as the basis for agencies to identify rules as exceeding statutory authorization. Any deregulatory effort will likely face swift legal challenge under the Administrative Procedure Act. And the novel use of AI tools is sure to raise a host of new legal questions.

Courts often examine deregulatory efforts for reasoned decision making under an arbitrary-and-capricious standard of review. The DOGE presentation repeatedly references the importance of agency policy staff and attorneys being intimately involved with the decision-making process. DOGE asserts the tool “enables agencies to comment and modify” the results, while it “automatically drafts all submission documents for attorneys to edit.” Yet the “policy and legal teams [must] make all the decisions.” This is a sage warning, but will agencies heed it in practice? And how will courts react while analyzing the AI-driven processes behind particular deregulatory efforts?

One efficiency the tool boasts is the ability to “analyze & respond to 100,000+ [public regulatory] comments” in a fraction of the time it would take a staffer. But this raises the question, will such review, summary, and response drafted by an AI tool and then later reviewed by a staffer meet the APA’s requirement that agencies give meaningful consideration to commenters’ filings?

And how will agency staff and courts deal with so-called hallucinations. Stories continue to proliferate about courts themselves issuing opinions that contain errors seemingly provided by AI drafters. Presumably these drafts were reviewed and given the judge’s stamp of approval before being issued. Once mistakes were identified, courts pulled them back and corrected the errors. But the federal rulemaking process is not so amenable to post hoc revisions on the fly. Agencies are usually stuck with the reasoning and administrative record they publish along with a final rule. And it is certainly foreseeable that a court would find an error-laden final rule to be arbitrary and capricious, even if the error is a minor one that is easily corrected.

While the use of AI in federal rulemaking raises novel legal questions, using it to comb through the Code of Federal Regulations has enormous potential to identify areas of duplication or deviation from statutory mandates. The sheer scale of an overgrown regulatory state not only burdens the regulated community but it also hampers a reform-minded administration’s ability to assess where changes are most needed or mandated by changes in law. An AI tool is perfectly situated to help sift through such large amounts of data and pinpoint places where agency staff should focus their efforts. New tools always require experimentation, refinement, and redeployment. The use of AI in federal rulemaking will be no different. But it’s heartening to see the Trump Administration’s willingness to experiment with something new.

The Brookings Institution hosted an essay by two professors, Raquel Muñiz and Rebecca Natow, profiling Loper Bright‘s impact on education law. They write:

Since the case was decided in 2024, Loper has been cited by courts as justification to restrain executive agency actions relating to education. In Tennessee v. Cardona (2025), a federal district court in Kentucky cited Loper to state that the court would employ “its independent judgment in interpreting Title IX,” before holding that a Department of Education regulation “impermissibly redefine[d] discrimination on the basis of sex for purposes of Title IX” and “must be set aside.” In Missouri v. Trump (2025) (previously Missouri v. Biden), the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals barred the Department of Education from canceling student loans under the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) program. In its opinion, the Eighth Circuit cited Loper to state that an executive agency’s interpretation of a statute should receive “respect” but “not supersede” a court’s interpretation.

Read the full essay here.

NRO’s Dan McLaughlin on the recent DOJ filing asking the D.C. Circuit to hold Loper Bright in abeyance on remand while the parties pursue settlement:

The Loper Bright and Relentless plaintiffs could still have a long voyage ahead in the appeals courts — unless the government listens to reason. But it seems that attention to the anomalous position taken by the DOJ and Commerce may be paying off: The government has entered into talks with the Loper Bright plaintiffs to settle the case, and any such settlement would necessarily entail at least some retreat from the original regulations.

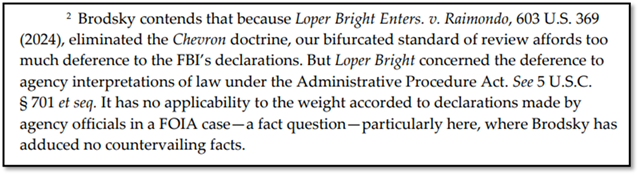

The Seventh Circuit has rejected an argument that Loper Bright impacts its standard of appellate review under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”). In Brodsky v. FBI—a case involving a confidential informant’s access to records about himself—the Seventh Circuit affirmed the lower court’s ruling that the FBI properly withheld material under Exemptions 3, 6, and 7, as well as appropriately refused to confirm or deny the existence of responsive records—a so-called “Glomar response.”

As part of his argument on appeal, the informant, Mr. Brodsky, insisted the elimination of Chevron deference foreclosed the Seventh Circuit’s “bifurcated standard of review,” as well as the weight it gives to declarations made by agency officials in FOIA cases. The Circuit rejected that argument, explaining Loper Bright had no bearing on deference to agency factual determinations on appeal.

Although the FOIA is part of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”), it has its own standard-of-review provision that requires a district court to review any “matter de novo.” 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B). Still, courts routinely afford agency declarations a presumption of good faith and, given the asymmetric distribution of knowledge between an agency and a requester about the content and character of responsive records, it can be difficult for a requester to challenge an agency’s factual claims. More disturbingly, the presumption of good faith often morphs into “substantial deference” in the context of withholding under Exemptions 1 or 3 whenever national-security interests are implicated. Such informal “deference,” as some have argued (here and here), undermines the FOIA’s promise of de novo review.

As a strictly textual matter, the FOIA’s de novo review standard only applies in the district court. The courts of appeal have not uniformly adopted a de novo standard for their review of lower courts’ FOIA decisions. While nearly all of them have, the Third and Seventh Circuits have taken a different approach. In the Seventh Circuit, for example, the appellate court will examine de novo whether the lower court had an adequate factual basis to issue a legally sound ruling. But then it applies a “clear error” standard to assess whether a record has, in fact, been properly withheld or redacted.

Such bifurcated review is odd. It is based on a defensible but highly idiosyncratic reading of the FOIA. But it also does not transgress the principles underlying Loper Bright. (Read my piece on Loper Bright and Exemption 3 for more about how it will impact FOIA jurisprudence.) The Seventh Circuit’s decision in Brodsky has given no indication that the court would defer to a lower court, let alone an agency, on any question of law. That kind of deference would be problematic. Read the Brodsky decision here.