Subscribe to Recasting Regulations to Sign up for Loper Bright Updates.

"*" indicates required fields

AFP Foundation’s Michael Pepson mentioned Lesko v. United States as a case to watch for understanding how Loper Bright might guide restraint over agency authority without Chevron deference earlier this year. At the time, the Federal Circuit had ordered en banc review to reconsider whether the Court of Federal Claims correctly upheld the Office of Personnel Management’s (“OPM”) overtime regulations. Last week, the full Circuit ruled in favor of OPM after applying the new Loper Bright paradigm for judicial review.

(more…)When the Supreme Court decided Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, overturning Chevron deference, it clarified the principle that federal agencies cannot extend their authority beyond what has been clearly authorized by Congress. In declaring that “statutes . . . have a single, best meaning,” the Court made clear that agencies must follow the law as written and not their policy preferences. Over the past year, this clarity has prompted many agencies to scrutinize long-standing policies, even those created before Chevron deference. The Trump Administration has even made such reevaluation a central pillar of its deregulatory agenda, as reflected in Executive Order 14219 and guidance from the Office of Management and Budget. The Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) new Title VI rule, which eliminates disparate-impact liability, is just one of the clearest and most recent examples of the real impact Loper Bright is having on the American regulatory space.

(more…)Jace Lington and Bennett Nuss discuss the implications of the Loper Bright decision on administrative law with guest Eli Nachmany. Eli’s forthcoming paper, “Deference Undisturbed,” examines the effects of the Loper Bright decision on prior cases decided under the Chevron framework. They discuss the open legal questions that remain after the end of Chevron, the role of Congress in shaping administrative law, and the future of various deference doctrines.

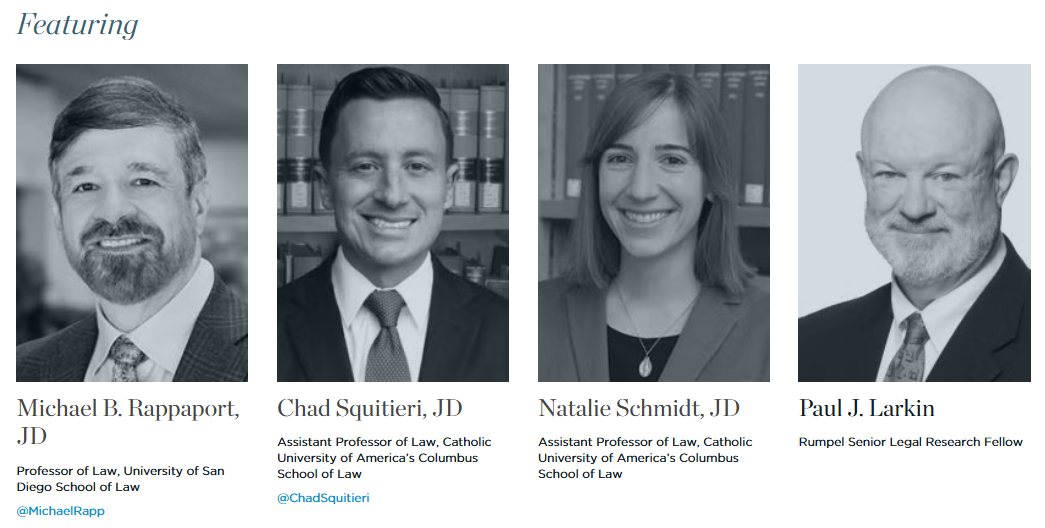

Separation of Powers Institute Professor Chad Squitieri hosted Professor Natalie Schmidt for a fascinating discussion about her article on the distinction between law and fact. The podcast covers formalism, functionalism, realism, agencies’ role in factfinding, and why the distinction between law and fact is critical following the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright.

Listen to the Episode:

Loper Bright overruled the Chevron doctrine and held that the APA requires courts to independently interpret statutes without deferring to federal agencies’ views on what the law is. In its wake, questions have arisen as to whether and how Loper Bright applies to the National Labor Relations Board’s interpretations of the National Labor Relations Act, a statute that predated the APA. And the NLRB has taken the position that even after Loper Bright, its interpretations of the NLRA are entitled to deference.

(more…)Earlier this week, the D.C. Circuit issued a major decision in American Gas Ass’n v. Department of Energy, upholding energy efficiency standards for residential gas furnaces and commercial water heaters. Although the case is obviously significant for the energy sector, it is equally noteworthy for its engagement with Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the Supreme Court’s 2024 decision that eliminated Chevron deference and reshaped statutory interpretation in the administrative-law context.

(more…)The Major Questions Doctrine After “Loper Bright”

Wednesday, November 12, 2025

12:00 p.m. – 1:00 p.m.Project on Constitutional Originalism and the Catholic Intellectual Tradition: In recent years, the major questions doctrine has been thought of as an exception to Chevron deference. In Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the Supreme Court ruled that Chevron deference violated the Administrative Procedure Act. What, then, is the status of the major questions doctrine in the wake of Chevron’s demise? Join us for a panel that will explore the past, present, and future of the major questions doctrine in light of Loper Bright.

On October 30th, in Bastias v. U.S. Attorney General, the Eleventh Circuit issued an opinion highlighting a growing debate in the lower courts after Loper Bright on how broadly statutory stare decisis shields Chevron-era precedent upholding agency actions. Loper Bright overruled the Chevron doctrine, holding that the APA requires courts to independently interpret statutes, which have a single best reading fixed at the time of enactment. But “[b]y doing so,” the Court wrote, it “d[id] not call into question prior cases that relied on the Chevron framework. The holdings of those cases that specific agency actions are lawful—including the Clean Air Act holding of Chevron itself—are still subject to statutory stare decisis despite our change in interpretive methodology.” In the wake of Loper Bright, lower courts have grappled with whether this passage refers to the specific agency decision upheld under Chevron or the agency’s interpretation of the statute, reaching differing conclusions.

In Bastias, much ink was spilled on this thorny and important question. In 2022, the Eleventh Circuit denied Bastias’s petition for review of a Board of Immigration decision that Bastias was deportable based on a 2018 Eleventh Circuit decision, Pierre v. U.S. Attorney General, deferring to the BIA’s interpretation of the Immigration and Nationality Act under Chevron. Bastias sought cert in the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted the petition, vacated that ruling, and remanded for further consideration in light of Loper Bright. The Eleventh Circuit has now once again denied Bastias’s petition. All three judges on the panel wrote separately, concurring in the judgement to explain their reasoning.

(more…)On October 21, the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs issued a memorandum seeking to streamline the review of deregulatory actions. The memo builds on Executive Orders 14129 and 14219, which direct agencies to repeal ten existing regulations for each new one and to ensure that existing regulations are squarely authorized by statute. We’ve previously covered EO 14219 and the role Loper Bright plays in that process.

Loper Bright’s corrective to the judiciary’s all-too-common deference to regulatory agencies provides a window through which the Trump Administration can undo decades of agency overreach. But they must be methodical and follow deregulatory procedures. The good-cause exception is an alluring shortcut that agencies should use only in the rarest of circumstances, not as a get-out-of-process-free card. Among the guidance OIRA recently provided to agencies are examples of times when they may invoke the Administrative Procedure Act’s (“APA”) good-cause exception to notice-and-comment procedures. OIRA writes:

The real target of this review is regulations that are, in the agency’s current view, facially unlawful — that is to say, where the unlawfulness is apparent to the agency after reviewing the text of the relevant regulation, the statute it implements, and other sources of law, such as the ten Supreme Court cases identified in the April 9 Memo. If the regulation is unlawful, as — for example — where the rule is inconsistent with the “single, best meaning” of the statute under Loper Bright, direct repeal under the APA’s “good cause” exception is appropriate. Or, if someone challenging the merits of the rescission would be relying on pure legal arguments for their challenge (e.g., arguing that the prior regulation did, in fact, reflect the best meaning of the statute), that fact reinforces the appropriateness of bypassing notice and comment.

As I argued last year, “I am leery of an attempt to invoke an APA good-cause exemption or using interim final rules to expedite deregulation because it risks jeopardizing the entire project. A blanket or cut-and-paste invocation of good cause to avoid notice and comment is too thin a reed to support such a large project when the inevitable barrage of litigation ensues.”

Mr. Valvo is chief policy counsel at Americans for Prosperity Foundation and one of the counsels representing the fishermen in Loper Bright.

American Legislative Exchange Council’s Nino Marchese writes in The Hill:

Loper Bright reminds the nation that final legal interpretation belongs squarely with the judiciary — a core thread of our jurisprudential fabric stretching all the way back to Marbury v. Madison. When judges are forced to bow before bureaucrats on questions of law, we risk not only implementing the policy preferences of unelected regulators, but also expanding executive branch “lawmaking,” eroding the separation of powers characteristic of our system.

Although Loper Bright cleared the way for our federal courts, it left state judiciaries untouched. Nearly two-thirds of the states continue to operate under some form of deference, many suffering under a jurisprudential fog of unclear or inconsistently applied precedent.

…

This year, more than 13 states have introduced aligned anti-deference bills, five of which — Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas — prevailed.