Subscribe to Recasting Regulations to Sign up for Loper Bright Updates.

"*" indicates required fields

In a long-awaited remand decision, the D.C. Circuit in Solar Energy Industries Ass’n v. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission upheld FERC’s regulatory interpretation of the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (“PURPA”). The Circuit previously sided with FERC last year when it concluded the agency’s position was “reasonable” under Chevron Step Two, in light of supposed statutory ambiguity. This week’s decision comes after the Supreme Court’s landmark overruling of Chevron in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo. Yet despite the end of Chevron deference, the Circuit still concluded that FERC’s reading of the law reflected “the best view of the statute.”

(more…)The Pacific Legal Foundation launched a new tool that “uses artificial intelligence to trace every federal regulation back to the law that supposedly authorizes it.”

The tool—which was developed by Patrick McLaughlin, a visiting research fellow at PLF—reveals whether Congress granted agencies broad, open-ended powers or gave them narrow, specific instructions. That distinction is crucial in the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent decisions in West Virginia v. EPA, which developed the major questions doctrine, and Loper Bright, which restored meaningful judicial review of agency power. By mapping the legal foundation of each rule, the Nondelegation Project highlights which regulations may now be vulnerable to challenge.

An accompanying explainer on the Nondelegation Project identifies the agencies with the highest number of general delegations:

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (3,309)

- Environmental Protection Agency (2,752)

- Agricultural Marketing Service (1,284)

- Food and Drug Administration (1,155)

- Department of Justice (661); Food Safety and Inspection Service (661)

On Friday, in Iowa v. Wright, the Eighth Circuit vacated an April 2024 Department of Energy regulation changing how it calculated the “petroleum equivalency factor” used to determine how car and truck manufacturers can use electric vehicles to comply with Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards set by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Two months after DOE issued the challenged regulation, the Supreme Court issued Loper Bright overruling the Chevron doctrine, which required courts to defer to agency statutory interpretations under certain circumstances. The Eight Circuit panel ruled that “the fuel content factor exceeds DOE’s authority under the substantive statute,” citing Loper Bright repeatedly in that portion of the opinion. Several states and the American Free Enterprise Chamber of Commerce brought the challenge.

(more…)During yesterday’s Senate Judiciary hearing on nominations, Senator Eric Schmitt (R-MO) questioned nominee to be United States Circuit Judge for the Third Circuit Jennifer L. Mascott on the impact of the Loper Bright decision.

This week, in Lopez v. Bondi, the Ninth Circuit denied a petition for rehearing of a panel decision upholding the Board of Immigration Appeals’ (“BIA”) conclusion that petty larceny convictions are “crimes of moral turpitude.” Judge Bumatay authored a dissent. While Lopez is ostensibly an immigration dispute, it may have much broader administrative law implications because of how the panel majority applied Loper Bright to the specific statutory interpretation questions at issue in that case. As Judge Bumatay put it:“This case is of rare importance. As the first to interpret Loper Bright in the immigration context, Lopez will govern hundreds of cases on the Ninth Circuit’s docket. But even more, this case will infect other areas of law—no doubt spreading to our broader administrative-law jurisprudence.” Underscoring the significance of the panel’s misapplication of Loper Bright, Professors Michael Kagan and Christopher Walker filed an amicus brief in support of rehearing en banc (which Judge Bumatay cites).

Judge Bumatay forcefully argues that Lopez’s reasoning is based on a fundamental misreading of Loper Bright that “conflicts with” that landmark decision for three reasons that independently justify en banc review: “First, Lopez favored agency deference rather than the best reading of the statute. Second, Lopez applied agency deference even without any statutory ambiguity. And third, Lopez refused to revisit Chevron-based precedent that is clearly irreconcilable with Loper Bright.”

Loper Bright “announced a sea change in how federal courts must treat the Executive Branch’s interpretation of the law,” Judge Bumatay wrote, emphasizing Loper Bright’s core teaching that “[c]ourts must independently interpret statutes and must not defer to an executive agency’s legal interpretations.” Loper Bright, of course,ended the Chevron regime, under which courts would give binding deference to agency statutory interpretations under certain circumstances. In the dissent’s view, “the panel took the extraordinary step of resurrecting Chevron under the alias of “Skidmore deference.” It did this by essentially putting the cart before the horse, jumping to whether the BIA’s conclusion that Mr. Lopez’s criminal convictions were “crimes of moral turpitude” was entitled to Skidmore respect, instead of first ascertaining for itself the best reading of the statute, as Loper Bright now requires. In this way, the dissent continues, “the panel abdicated the judicial role and just applied Chevron deference by another name.”

The dissent also took issue with the panel’s decision “to ‘afford’ the BIA’s interpretation of the” law ‘Skidmore deference,’” even though the plain language of the statute “forecloses Lopez’s [pardon waiver] argument.” In other words, even though the panel found that the statute was unambiguous, it still granted the agency’s interpretation respect under Skidmore. In the dissent’s view, “This makes little sense. If the statutory text resolves the matter unambiguously, then we stop there. We don’t then check whether the Executive branch agrees with the plain meaning. . . . So deference and respect have nothing to do with this question.”

Finally, the dissent suggested rehearing en banc was warranted because “the panel misread Loper Bright to preclude three judge panels from revisiting circuit precedent based on the now-defunct Chevron doctrine.” This portion of the dissent brings to the surface an issue that has been causing confusion in the lower courts: the proper scope of statutory stare decisis for past cases decided under the now-repudiated Chevron doctrine. The Supreme Court said in Loper Bright that in overruling Chevron, it “d[id] not call into question prior cases that relied on the Chevron framework. The holdings of those cases that specific agency actions are lawful—including the Clean Air Act holding of Chevron itself—are still subject to statutory stare decisis despite our change in interpretive methodology.” To date, lower courts have reached differing conclusions on whether this passage refers to the specific agency decision upheld under Chevron or, alternatively, the agency interpretation of the statute that was upheld under Chevron. In other words, does statutory stare decisis travel with the specific agency decision or the agency’s interpretation of the statute that was used to justify the agency decision upheld under Chevron. Judge Bumatay interprets this passage in another way that may be worth paying attention to, writing that “Loper Bright’s statement about ‘prior cases’ refers to its prior cases—not ours.” The implication of this reading of Loper Bright appears to be that at least under the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Miller v. Gammie, lower court precedent upholding agency decisions under Chevron is not entitled to statutory stare decisis, which, if ultimately accepted, may be a big deal.

In the dissent’s view, the panel misread and misapplied the statutory stare decisis passage in Loper Bright in at least two ways. “First, Loper Bright was a clear ‘intervening United States Supreme Court decision’” under Miller that required the panel to revisit Chevron-era circuit precedent without granting it stare decisis effect. The dissent argued that “the panel overread” the sentence in Loper Bright on stare decisis “to preclude lower courts from revisiting lower-court precedents that relied on Chevron.” To the contrary, “any Ninth Circuit precedent that relies on Chevron to defer to an agency’s interpretation of the law is ‘clearly irreconcilable’ with Loper Bright.” The dissent continued: “neither Loper Bright nor our stare decisis factors precluded us from revisiting and overruling Chevron-based precedent.” Second, the panel’s declaration that only a new agency interpretation permits us to revisit Chevron-based precedent lets the Executive branch—not the courts—dictate the interpretation of the law.” In the dissent’s view, that approach “defies sound logic— and worse still, it resurrects Chevron.”

Judge Bumatay sums up where the dissent parts ways with the panel opinion’s application of Loper Bright thus: “Loper Bright represented one of the most dramatic changes in how courts should do statutory interpretation. Even so, Lopez acts as if nothing has changed.” That captures well why the panel opinion should not be allowed to stand. And for those who are interested the debate over Loper Bright’s impact on statutory interpretation, administrative law, and the power relationship between courts and agencies, Judge Bumatay’s thoughtful dissent from denial of rehearing en banc in Lopez is worth reading. It will be interesting to see whether Mr. Lopez seeks Supreme Court review on one or more of the Loper Bright implementation questions and whether the Court grants cert.

My latest op-ed in the Washington Reporter uses FOIA docs from the CHIPS Act implementation to demonstrate how ambiguous laws empower unelected bureaucrats and undermine democratic accountability:

When Congress rejected sweeping child care subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act, the Biden administration’s Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo reportedly told her staff, “if Congress wasn’t going to do what they should have done, we’re going to do it in implementation.”

That wasn’t just rhetoric — it became a blueprint for how the Biden administration would abuse a bill meant to support the domestic production of semiconductors, the CHIPS and Science Act, to instead impose progressive social policies through administrative fiat.

After more than two years of government stonewalling in Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) litigation, the Americans for Prosperity Foundation uncovered how the Biden administration’s Department of Commerce made political decisions to burden domestic chip manufacturers with additional requirements and mandates beyond what the statute allowed, undermining the national security argument that was key the bill’s passage.

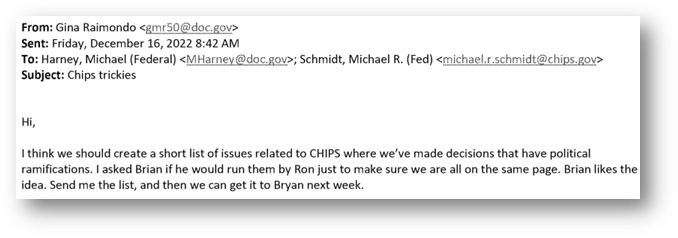

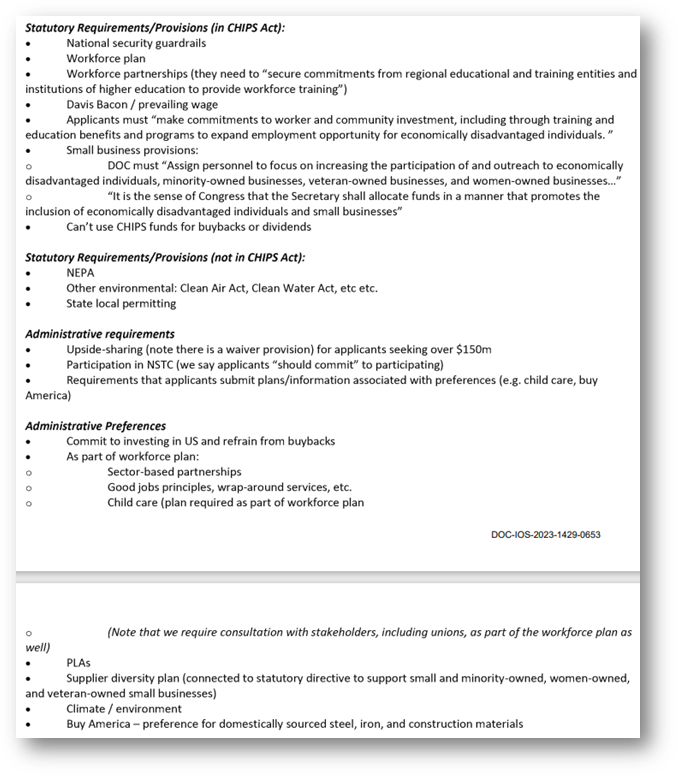

Raimondo knew they exceeded the statute’s bounds, which is why she preemptively asked her staff to come up with “a short list of issues related to CHIPS where we’ve made decisions that have political ramifications” (emphasis added).

Another email obtained in litigation revealed how Raimondo advisors outlined the various “Administrative requirements” and “Administrative Preferences” that were not included in the “Statutory Requirements.”

AFP Foundation Senior Policy Counsel Ryan Mulvey joined Montana Talk’s Aaron Flint live from the Western Caucus Foundation meeting to discuss Loper Bright.

Featuring:

- Ryan Mulvey, Senior Policy Counsel, AFP Foundation

- Graham Owens, Policy Fellow, Americans for Prosperity

- Aaron Flint, Host, Montana Talks

Interview starts at 28:20.

Bloomberg Law’s UnCommon Law podcast finishes its series on the “story behind the fishing industry’s Chevron doctrine challenge.” This episode is on: “After Loper Bright, Congress Weighs Sweating the Small Stuff”

In this season finale, we hear from a current and a former senator on opposite sides of the aisle who both argue that Congress must reclaim its constitutional role. They agree that decades of delegating authority to agencies has weakened the legislature, but they diverge on what should happen next. Should lawmakers strip out vague catchall words to limit agency discretion? Or should Congress work more closely with agencies to ensure workable, expert-informed legislation?

Featuring:

- Sen. Eric Schmitt, R-Mo.

- Former Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, D-N.D.

A recent cert petition asking the Supreme Court to vacate the Sixth Circuit’s decision in Tennessee v. Kennedy, and remand with instructions to dismiss the case as moot under United States v. Munsingwear, highlights an important Loper Bright implementation question that the Court may need to resolve in a future case: the scope of statutory stare decisis protection of agency interpretations of statutes that were upheld by courts under the Chevron regime. (Recasting Regulations previously discussed this case here.)

In overturning Chevron, the Loper Bright Court granted some protection to prior agency actions upheld under the Chevron regime. The Court went out of its way to make clear that Loper Bright “do[es] not call into question prior cases that relied on the Chevron framework” and that “[t]he holdings of those cases that specific agency actions are lawful . . . are still subject to statutory stare decisis[.]”

As Tennessee v. Kennedy illustrates, there appears to be some confusion in the lower courts as to whether only the specific agency decisions upheld under Chevron are entitled to statutory stare decisis or, alternatively, the agency’s statutory interpretation itself receives that protection. The panel majority’s revised opinion concluded that “a ‘specific agency action’ attaches to an agency’s particular construction of a statute,” citing Loper Bright. But in dissent, Judge Kethledge persuasively explains that that passage of Loper Bright is best read to limit statutory stare decisis protections to the particular regulations that were upheld under Chevron.

The answer to that question matters because if statutory stare decisis travels with the agency’s statutory interpretation, it would allow a form of de facto Chevron deference to continue to shield those interpretations indefinitely. This would, to some extent, limit Loper Bright’s core holding that courts must independently interpret statutes including in cases involving agencies.

This cert petition is worth watching. And it will be interesting to see if the Court GVRs Tennessee v. Kennedy under Munsingwear or allows that decision to remain on the books in the Sixth Circuit.

Bloomberg Law’s UnCommon Law podcast continues its series on the “story behind the fishing industry’s Chevron doctrine challenge.” This episode is on: “Chevron Deference Is Dead. Is the Administrative State Still Alive?”

In just the first six months after Loper Bright was decided, courts cited the case more than 400 times, according to a Minnesota Law Review article. Lower federal courts invalidated new agency rules almost 84% of the time. This has affected policies ranging from net neutrality to labor regulations to environmental protections. We delve into how Loper Bright has already reshaped American regulatory policy.

Featuring:

- Helgi Walker, partner at Gibson Dunn and co-chair of their administrative law and regulatory practice group

- Rebecca Rainey, senior labor department reporter for Bloomberg Law

- Cary Coglianese, professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and director of the Penn Program on Regulation