Loper Bright Cited in D.C. Circuit’s Decision in Alien Enemies Act Case

By

| March 28, 2025

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit has denied the federal government’s emergency request to stay a pair of temporary restraining orders in J.G.G. v. Trump, a high-profile case challenging the Trump Administration’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 (“AEA”). Somewhat unexpectedly, the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo was prominently cited by Judge Patricia Millet in her concurrence. Millet offered Loper Bright as support for the notion that important questions of statutory construction—here, the scope of review under the AEA and the meaning of predicates for presidential action—were squarely within the judicial ken and thus not non-justiciable under the political-question doctrine. It remains unclear whether that assertion is correct or if Loper Bright impacts the political-question doctrine at all.

The AEA provides that “[w]henever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government,” or an “invasion or predatory incursion” against the territory of the United States by a “foreign nation or government,” the President shall have the authority, following issuance of a “public proclamation,” to detain and remove “all native, citizens, denizens or subjects” of that hostile nation or government who are over the age of fourteen. On its face, the AEA provides the executive branch with seemingly extraordinary discretion to determine whether there is a qualifying “invasion or predatory incursion,” or even whether there exists a state of “declared war.”1 Once those preconditions are established, the President also seems to enjoy broad authority to detain and deport noncitizens to which an AEA proclamation applies.

Background on J.G.G. Case

The J.G.G. case involves five Venezuelan nationals whom the Administrations has determined are members of the international criminal gang and designated terrorist organization, “Tren de Aragua” (“TdA”). In mid-March, President Trump issued a proclamation under the AEA declaring TdA to be “perpetrating, attempting, and threatening an invasion or predatory incursion,” either “directly”—that is, as a de facto government—or as an effective agent of the Venezuelan government. The plaintiffs contest the proclamation, as applied to them, and seek a court order to prevent their removal. So far, they have successfully certified a provisional class on behalf of all suspected TdA members, as well as temporary restraining orders suspending the government’s removal efforts.

The J.G.G. case is procedurally complex and implicates deeply contested and difficult questions about jurisdiction, the availability and scope of judicial review, venue, justiciability and the political-question doctrine, and procedural regularity.

The Impact of Loper

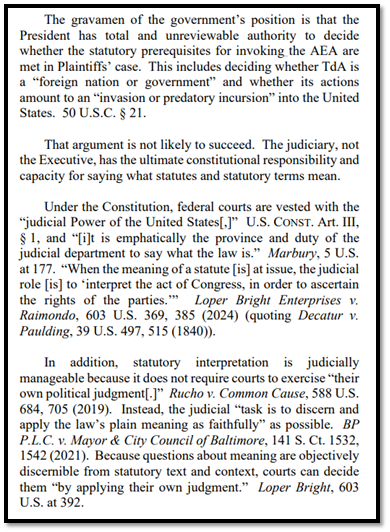

As far as the reference Loper Bright is concerned, Judge Millet used the decision to support her argument that the government cannot sidestep judicial review of its use of the AEA by claiming sole interpretative authority for when the AEA’s preconditions are triggered:

Like Judge Henderson, Millet’s argument about the scope of review under the AEA seems to depend on her view that it is the job of courts to interpret statutory terms, even when those terms are found in statutes implicating core Article II authority. On her view, insofar as statutory language can be construed without reference to political judgments, the political-question doctrine does not apply. Thus, again citing Loper Bright, Judge Millet insists the AEA’s phrases “invasion,” “predatory incursion,” and “foreign nation or government” are all “objectively discernable from statutory text and context,” and present an question of interpretation rather than presidential discretion. “The judiciary can resolve this disagreement with settled tools of statutory construction,” she writes.

Judge Walker, who dissented from the denial of the government’s emergency motion, did not address the scope of judicial review under the AEA or whether the political-question doctrine applied. He argued instead that the government should win for a “technical, but important, reason,” namely, that the plaintiffs’ “claims sound in habeas” and should have been raised in Texas, where they are currently detained. In this regard, Walker observed that “the few [AEA] cases on the books almost invariably arose through habeas petitions[.]”