Everything wrong with the FOIA process, in one single email

By

| January 29, 2025

If you’ve ever filed a public records request, you may have experienced delays, improper denials, lack of communication, or all of the above. What’s less common is when an agency gives a requester a responsive record and then demands it be given back or destroyed, also known as a “clawback.” In 2022, the Federal Trade Commission released to AFP Foundation an email in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit and then, seven months later, tried to make us delete it after claiming they inadvertently failed to redact portions of the email as subject to the attorney-client privilege exemption of the FOIA.

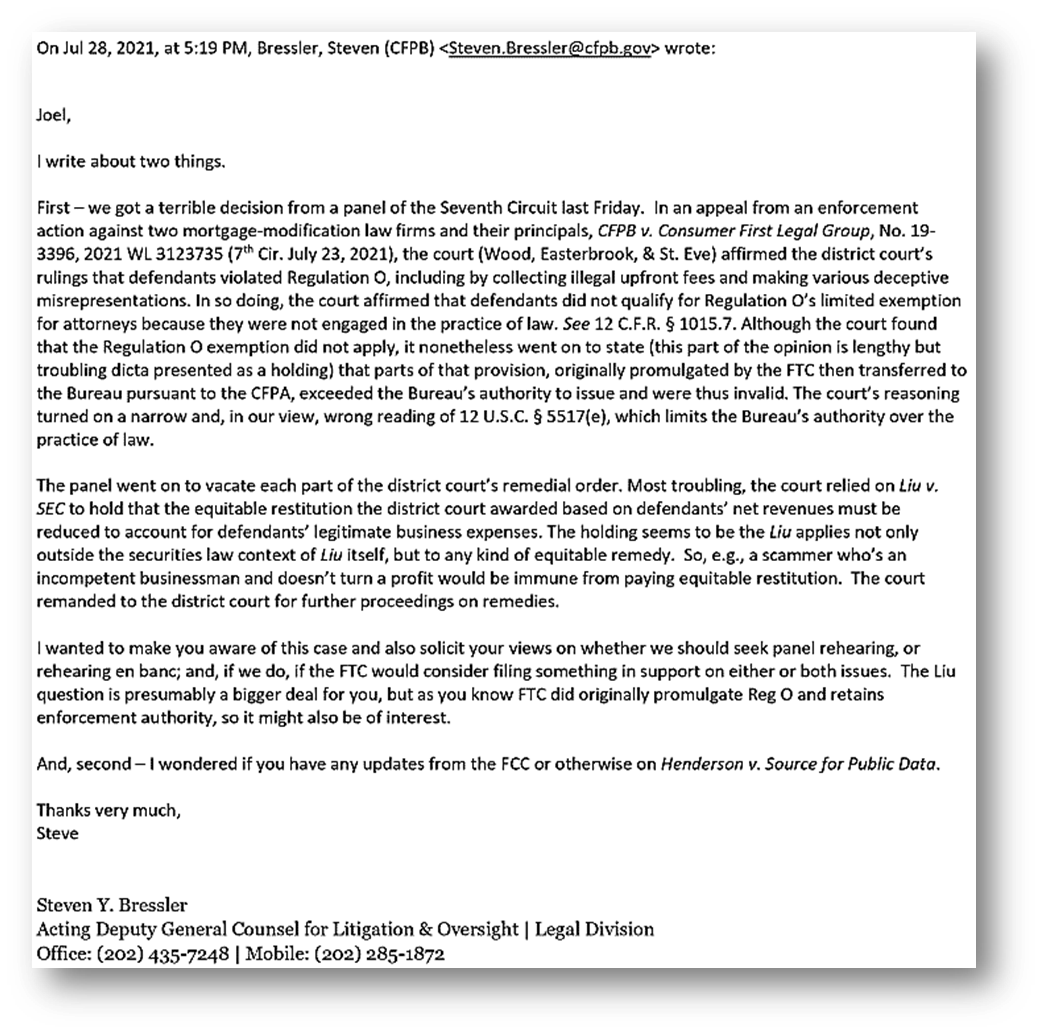

The record in question is a July 2021 email from Steven Bressler, then Acting Deputy General Counsel for Litigation & Oversight at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, to Joel Marcus, then Deputy General Counsel at the Federal Trade Commission, regarding a decision in a Seventh Circuit case and seeking updates on the status of another legal case. The email summarizes a court case, asks if the FTC would be interested in submitting an amicus brief on a potential panel rehearing or hearing en banc, and asks a question.

But the government treated the release of this innocuous message as a five-alarm fire despite the fact that they produced it almost seven months earlier. The agency demanded AFP Foundation destroy or seal the record and argued that failing to do would “have a chilling effect on the FTC’s free exchange of ideas between its staff and counsel.” We refused because allowing agencies to clawback records sets a bad precedent and is unsupported by statute or case law.

While agencies argue that requesters aren’t harmed by agency clawbacks, there are three major problems with agreeing to doing so. As my colleague Ryan Mulvey wrote in a recent amicus brief before the D.C. Circuit in Human Rights Defense Center v. U.S. Park Police:

First, the release of a record under the FOIA typically moots any further dispute over its withholding, even if the agency claims disclosure was inadvertent. Clawback violates that principle. Second, the equitable power of a court to enforce the terms of the FOIA should always be exercised in favor of disclosure. Clawback offends the very purpose of the FOIA and is not an appropriate remedial power. Third, clawback amounts to a prior restraint and infringes on First Amendment protections.

And on January 24, the D.C. Circuit agreed. In its opinion rejecting the Park Police’s position, the court confirmed that the “primary function” of clawback isn’t to “support a core judicial authority, but to fill a perceived hole in the FOIA statute by enabling the government to put the proverbial cat back in the bag.”

The effects of that decision have been felt immediately. For example, in an ongoing FOIA case in the District of Maryland, the Department of Homeland Security withdrew its motion to compel attorney Mark Zaid to disclose the identity of third parties who were given records the agency believed were exempt from disclosure but accidentally produced during the litigation.

Simply stated, the FOIA doesn’t allow for clawback as an exercise of inherent court authority.

At the end of the day, the DOJ and FTC agreed to waive any claim to the return or destruction of the record in our FOIA litigation in order to avoid a fight over three separate records we believe were unlawfully redacted. A cynical person might say they were suddenly okay with “chilling” FTC employees’ exchange of ideas as long as it unburdened them from having to try to convince a judge they were following the law—a situation exceedingly difficult to do in light of the D.C. Circuit’s HRDC opinion.

Clawback demands are emblematic of how federal agencies approach transparency as something to be avoided and to fight about rather than err on the side of disclosure. Hopefully, they are now a practice relegated to the past.

Georgia Supreme Court Rules Constitutional Challenge To Direct-Sales Ban May Proceed