Fifth Circuit Upholds EPA Disapproval of Texas Ozone Implementation Plan Under Loper Bright

By

| September 30, 2025

Last week, the Fifth Circuit issued a significant decision in Texas v. EPA, denying Texas’s petition for review of the Environmental Protection Agency’s (“EPA”) disapproval of a State Implementation Plan (“SIP”) under the Clean Air Act (“CAA”). The case is notable not only for its implications for interstate air pollution regulation, but also for its application of Loper Bright.

Texas and the Clean Air Act’s Good Neighbor Provision

As part of the CAA, Congress created the so-called “Good Neighbor Provision,” which obligates “upwind” states to create implementation plans that ensure pollution emissions will not prevent “downwind” neighboring states from attaining federal air-quality standards. The EPA reviews these plans—or SIPs—to ensure they comply with the CAA’s various requirements. The whole process can be scientifically complex.

In 2012, Texas submitted an SIP concluding that the state’s contributions to ozone pollution in neighboring jurisdictions were so insignificant as not to require any mitigating action. The EPA reviewed the plan and, after notice-and-comment, rejected it. The agency concluded the SIP was not only legally inadequate and unsupported by sufficient scientific analysis, but that it contradicted the EPA’s own data modeling, which painted a different picture about Texas’s contributions to the violation of federal ozone standards in neighboring states. After the EPA finalized its own direct implementation plan for Texas, the state filed a petition for review with the Fifth Circuit.

The Fifth Circuit’s Reasoning: Loper Bright and Delegations of Discretionary Authority

The Fifth Circuit denied Texas’s petition and upheld the EPA’s federal implementation plan. In terms of how it relied on Loper Bright, the Texas court acknowledged that the end of Chevron deference marked a paradigmatic shift in judicial methodology: “Under [Section] 706, ‘agency interpretations of statutes’ are reviewed without deference.” Yet sometimes “a statutory delegation of authority ‘leaves [the] agency with flexibility.” In those instances, a court’s job is to recognize a delegation of regulatory authority, fix the boundaries of the delegation, and “ensure[] the agency has engaged in ‘reasoned decisionmaking.’”

Applying this framework, the Texas court independently assessed the EPA’s interpretation of the “Good Neighbor Provision” and concluded the agency’s reading—namely, requiring SIPs to address both nonattainment and maintenance areas, including future risks—was consistent with the CAA’s text and overall structure. The Circuit also rejected Texas’s arguments that the EPA’s delay in acting on the SIP submission voided its subsequent actions. Given the lack of any express consequences for noncompliance with timing provisions in the relevant statutory text, the Texas court expressed deep discomfort in inferring prescriptive limits on the EPA’s authority. (On this point, Judge Jerry Smith dissented, proposing that vacatur for procedural tardiness would be the correct outcome.)

With respect to Texas’s substantive challenges, the Circuit held it would be improper to disallow the EPA to question the scientific soundness of SIPs. Although acknowledging the EPA “lack[ed] ‘authority to question the wisdom of a State’s choices of emission limitations,’” the Texas court warned that this lack of authority was “not a license [for a state] to submit a SIP that sets aside ‘the national standards.’” In other words, substantive compliance review by the EPA was not a merely procedural formality.

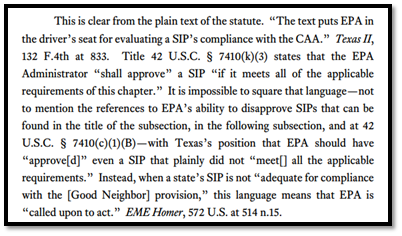

In a similar vein, the Circuit rejected Texas’s argument that the CAA “delegates unreviewable discretion to the states to bind the EPA and thereby this court to creative misreadings of the statutory requirements.” Not only would that have created an unworkable regulatory regime—one where the states adopt different readings of the CAA, or advance different theories of causation about downwind pollution, that limit the EPA’s substantive review of SIPs in contradictory ways—but it would inevitably foreclose Article III courts from providing a single, independent “best” reading of the law. Indeed, that result would seemingly undercut the entire purpose of the Good Neighbor Provision, which is to “address interstate externalities through federal statute” and under nationally managed standards.

Second, the Texas court affirmed the EPA’s reading of the Good Neighbor Provision to “prohibit” emissions that either “significantly contribute to nonattainment” or “interfere with maintenance” in any state. This “disjunctive” provision, according to the “[c]anons of construction,” provided alternative grounds for the EPA to disapprove Texas’s SIP. Importantly, when considering the precise meaning of “nonattainment,” the Texas court noted the persuasiveness of the EPA’s “consistent practice” of interpreting the CAA, as well as “its expertise in the factual predicates of administration in this scientifically complex area.”

The Significance of Texas v. EPA: Loper Bright and Scientific Expertise

More than anything, the Texas decision provides insight into how Loper Bright might shape judicial review in the environmental law space and, more generally, whenever statutes involve complex technical or scientific issues.

One of the open questions, after Loper Bright, is what it means for an agency interpretation of law to “rest on factual premises within” an agency’s “expertise.” The Loper Bright court suggested that such expertise would have the “power to persuade,” if not the “power to control,” a court’s judgment about the meaning of a statute. The Texas court, citing its own Chevron-era precedent together with Loper Bright, put the proposition in slightly different (and perhaps more direct) terms: “‘A reviewing court must be ‘most deferential’ to the agency where . . . its decision is based upon its evaluation of complex scientific data within its technical expertise.”

Yet there is an obvious tension between de novo review and “deference” to agency interpretations based on supposed expertise. That tension grew over time under the Chevron regime, as courts deferred to a greater range of agency actions. At least in cases where there is some express delegation to an agency to regulate and “fill out” the terms of a statute, respect for scientific or technical expertise might make some sense in delineating the boundaries of the delegation—to say nothing of how action might be review under “hard look” review. But Loper Bright is also clear that courts should not carelessly abdicate their responsibility for providing an independent, best reading of the law simply because a case involves matters of great complexity.

Whether or how the Supreme Court might provide further guidance on this front is further complicated by dicta in Seven County v. Eagle County that Baltimore Gas & Electric v. NRDC remains “black-letter administrative law.” Under the Baltimore Gas doctrine, “when an agency makes . . . speculative assessments or predictive or scientific judgments . . . a reviewing court must be at its ‘most deferential.’” Only time will tell whether that approach can coexist with a robust reading of Loper Bright.

AFP Foundation Files Amicus Brief in Relentless v. Department of Commerce