Seventh Circuit Declines to Apply Loper Bright to Modify Standard of Appellate Review on Fact Issues in FOIA Cases

By

| July 21, 2025

The Seventh Circuit has rejected an argument that Loper Bright impacts its standard of appellate review under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”). In Brodsky v. FBI—a case involving a confidential informant’s access to records about himself—the Seventh Circuit affirmed the lower court’s ruling that the FBI properly withheld material under Exemptions 3, 6, and 7, as well as appropriately refused to confirm or deny the existence of responsive records—a so-called “Glomar response.”

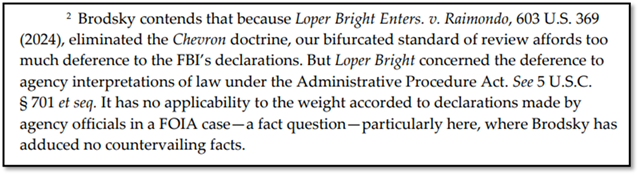

As part of his argument on appeal, the informant, Mr. Brodsky, insisted the elimination of Chevron deference foreclosed the Seventh Circuit’s “bifurcated standard of review,” as well as the weight it gives to declarations made by agency officials in FOIA cases. The Circuit rejected that argument, explaining Loper Bright had no bearing on deference to agency factual determinations on appeal.

Although the FOIA is part of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”), it has its own standard-of-review provision that requires a district court to review any “matter de novo.” 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B). Still, courts routinely afford agency declarations a presumption of good faith and, given the asymmetric distribution of knowledge between an agency and a requester about the content and character of responsive records, it can be difficult for a requester to challenge an agency’s factual claims. More disturbingly, the presumption of good faith often morphs into “substantial deference” in the context of withholding under Exemptions 1 or 3 whenever national-security interests are implicated. Such informal “deference,” as some have argued (here and here), undermines the FOIA’s promise of de novo review.

As a strictly textual matter, the FOIA’s de novo review standard only applies in the district court. The courts of appeal have not uniformly adopted a de novo standard for their review of lower courts’ FOIA decisions. While nearly all of them have, the Third and Seventh Circuits have taken a different approach. In the Seventh Circuit, for example, the appellate court will examine de novo whether the lower court had an adequate factual basis to issue a legally sound ruling. But then it applies a “clear error” standard to assess whether a record has, in fact, been properly withheld or redacted.

Such bifurcated review is odd. It is based on a defensible but highly idiosyncratic reading of the FOIA. But it also does not transgress the principles underlying Loper Bright. (Read my piece on Loper Bright and Exemption 3 for more about how it will impact FOIA jurisprudence.) The Seventh Circuit’s decision in Brodsky has given no indication that the court would defer to a lower court, let alone an agency, on any question of law. That kind of deference would be problematic. Read the Brodsky decision here.